Can technology alone solve urban challenges?

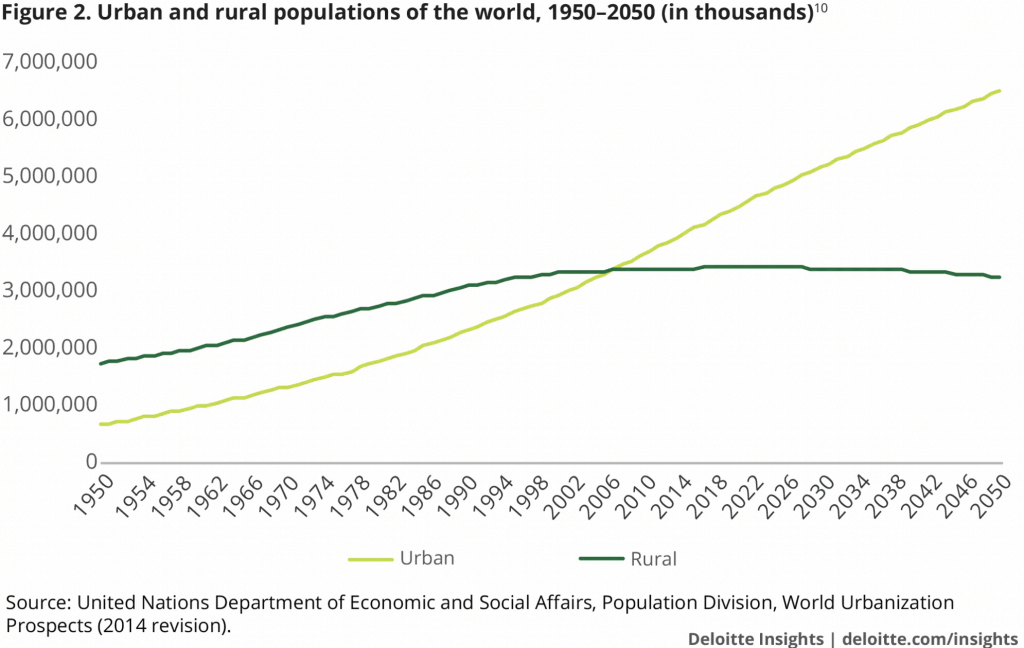

Rates of urbanization are rising in a big way. It’s projected that by 2050, more than two-thirds of the world will live in urban areas. In today’s world (particularly in 2020) there’s a multitude of urban challenges, and they will only be exacerbated as populations continue to rise.

Whether its issues with energy, transport, health, inequality, the environment – technology has long been touted as the answer. This stands to reason, as innovation in IT has irrevocably changed people’s lives – why shouldn’t this work for cities?

Enter smart cities.

Popularised by IBM in 2009 in the Smarter Cities campaign, these projects have seen tremendous success becoming the conduit between the tech industry and city governments. The common thread of these projects is solving urban challenges by harnessing the power of big data, sensors, and automation.

Whilst this has been an important development in our cities, problems still remain unsolved. There are cases where unforeseen side effects have emerged from embracing smart city solutions. So is it time to ask ourselves, can technology solutions truly solve urban challenges alone?

The problem with smart cities

Since 2009, the world’s largest IT solutions companies have equipped ‘smart cities’ as a go-to-market buzzword. Urban innovation has now become synonymous with becoming a smart city. AI and sensors would run services and utilities, automating processes, and giving policymakers more tools to make decisions. These large, expensive deployments promise to solve the fundamental problems through the increased use of data.

It’s often assumed by many big tech organisations that innovations can be implemented in one location and that it will work universally. Typically, solutions are bought off the shelf, with little understanding of what the unique challenges are to that city or local government. What is becoming apparent is the one size fits all approach doesn’t work. Solutions need to work in conjunction with citizens and local governments.

In terms of urban innovation, Uber is a case in point. Their aggressive go-to-market strategy implemented to cities globally is now finding resistance as many governments and citizens want some give and take from the relationship. The company is now backtracking and taking heed of what local authorities are lobbying for. This certainly applies to many smart city projects, where the priorities of cities, multinational corporations and the public sector often struggle to align, leading to unforeseen, negative consequences.

‘By 2023, Gartner predicts that 30 per cent of smart city projects will be discontinued for three main reasons — an inability for technology to cope with growing demand, residents’ worries about how data is used and the value of smart cities being less than expected.’

This includes the topic of interoperability where local councils find customization of their new smart city services difficult. Many of these products are not designed to work together as an ecosystem, meaning that integrations with other third parties are tough and vendor lock-in is a common challenge This becomes an issue when new problems emerge, local authorities need the flexibility to adapt their solutions and find new tools. This is a case where governments and therefore citizens do not control their technologies but are shaped by it.

What’s the urban challenge?

Many local governments want to become smarter. It’s become a badge of honor, a sign of progress to be a ‘smart city’, but is it completely necessary? Many solutions that are sold promise to bring endless benefits, but without the necessary support or understanding of the challenge, it may be useless. The one size fits all simply isn’t an approach that can be accepted.

Because of the scale of these solutions, they are largely implemented by corporates who, by their very nature, move slowly. Can these organisations be expected to work with each city and understand their individual problems and then adapt their solution to suit them? Can this technology be used by non-technical people? Is it helpful for a range of stakeholders in councils or will it be wasted?

Ultimately, the technology needs to work for the authority and the citizens and if it fails to do that, then what’s the use? There typically is the fascination with large bureaucratic organisations to crave digital transformation and revolutionise experiences for citizens and the public servants, but focus entirely on the technology, rather than the transformation element.

It must be remembered that technology alone cannot solve complex urban challenges. It needs to be utilised by the people who understand the unique challenges that their citizens face. Once technology gets in the way of this, it ceases to be smart or necessary.

“Smart cities are not automatically ones with the highest level of tech, nor the most integrated infrastructures. They are the ones that respond to the needs of their citizens in the best ways possible.”

Mark Elliott, CivTech Scotland

We need to be careful that we don’t prioritise the technology over what the problem actually is. Technology for technology’s sake simply is an expensive distraction over finding the right solution for the problem.

If technology is the answer, then what’s the question?

Nitrous has been working on a new urban innovation framework that places the city at the centre of innovation, placing a priority on challenges, rather than IT. Technology should be used as a tool, rather than the be-all and end-all. City and citizen challenges should come first in this equation, with tech as an enabler. In our CityTech framework, this is what we see as a priority to move forward:

Pre-procurement collaboration

For many procurement professionals, the breadth of technology solutions out there from large multinationals and SMEs is dizzying and hard to get a grip of. Moreover, innovative solutions may not, on the face of it, look appropriate. This is where engagement of an ecosystem of innovators is critical to understand the options before the procurement process. This way, local governments can make informed decisions about buying solutions and leverage joint-buying of a solution across multiple authorities.

Challenge-based procurement

Instead of procurement teams defining what they want to procure, why not broadcast the problems for innovators to solve? This takes the onus away from the buyers and pushes it out to the market to solve. This helps local governments define what they need in terms of a solution delivering a higher level of innovation and customizability for that city. In addition, challenges may expose the need for a softer approach than a full technology deployment.

Iteration and interoperability

The challenge with smart city platforms is that they risk becoming obsolete by the ever-changing demands of cities. If these technologies cannot be customized to suit the needs of citizens, then they are doomed to fail and cities will be stuck, waiting for updates. To counter this, greater engagement with SMEs to provide bespoke solutions would help keep a technology-specific enough for a city’s needs. These should be easily swapped out for more relevant technology if the need comes.

Open data

Cities should have ownership of their own data and it shouldn’t be restricted to the company which gathers it. The moment that data ownership is taken into question, there will always be a problem with urban innovation. Citizens could be alienated from the process when they should be seen as the enablers.

Ultimately, technology should be recognised as a tool, rather than the ultimate solution. It’s time we prioritise problems over shiny new solutions and look to the future of urban innovation.

Interested in the next generation of urban innovation?

Register today and receive our new framework for urban innovation with CityTech in January.